Brainstorming is an important prewriting tool, but it can also help you move past "writer's block" when you feel that you just aren't getting to the point you want t make. Brainstorming can help you take all the information you have about a character or a situation, and find the main point you want to make with that information.

Drawing conclusions is an important part of the writing process, and it is important to the reader. The following prompt will help you develop showing description, and then take it one step further by drawing a conclusion based on your descriptive brainstorming.

Prompt:

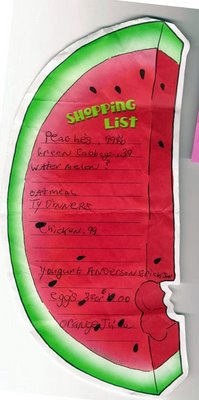

- Make a list of the big things and little things you'd never, in a million years, lend to your best friend - and after each, try to come up with a reason why not.

- When you finish your list, write one sentence that sums up both the things you've listed and the reasons why you wouldn't lend them to your best friend.

- Use that sentence as the basis for freewriting a short narrative piece.

You will choose between this exercise and yesterday's exercise, "Description - Showing Not Telling" to write a 250 word brief narrative piece to post on your blog. Please see your weekly assignment sheet for details